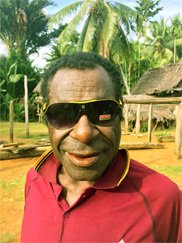

Karim tribe

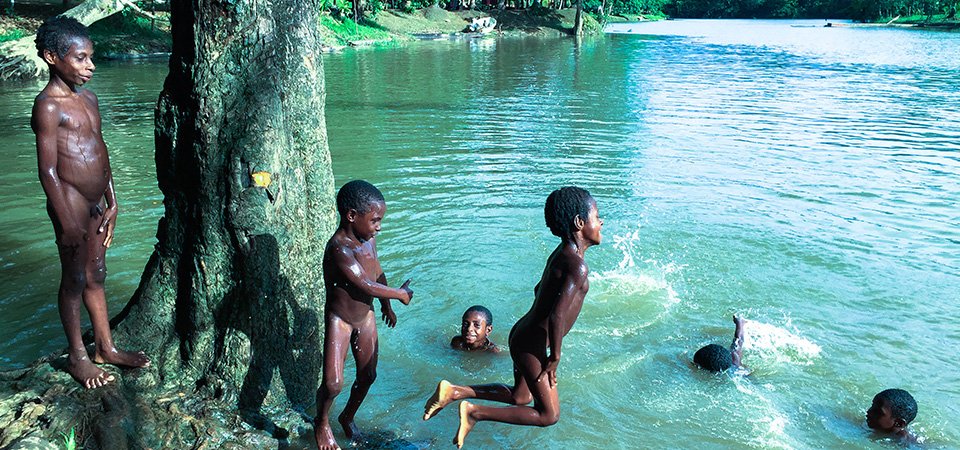

On the banks of the Karawari River, members of the Karim tribe hunt crocodiles and fish and live in traditional houses on stilts. The tribe is divided into smaller clans, each with its own totem. Karim legend says that each clan was created out of the body of its totem animal.

![]() Yimas, Papua New Guinea, S 4 40'45.9" E 143 32'33.7"

Yimas, Papua New Guinea, S 4 40'45.9" E 143 32'33.7"

![]() 700 people

700 people

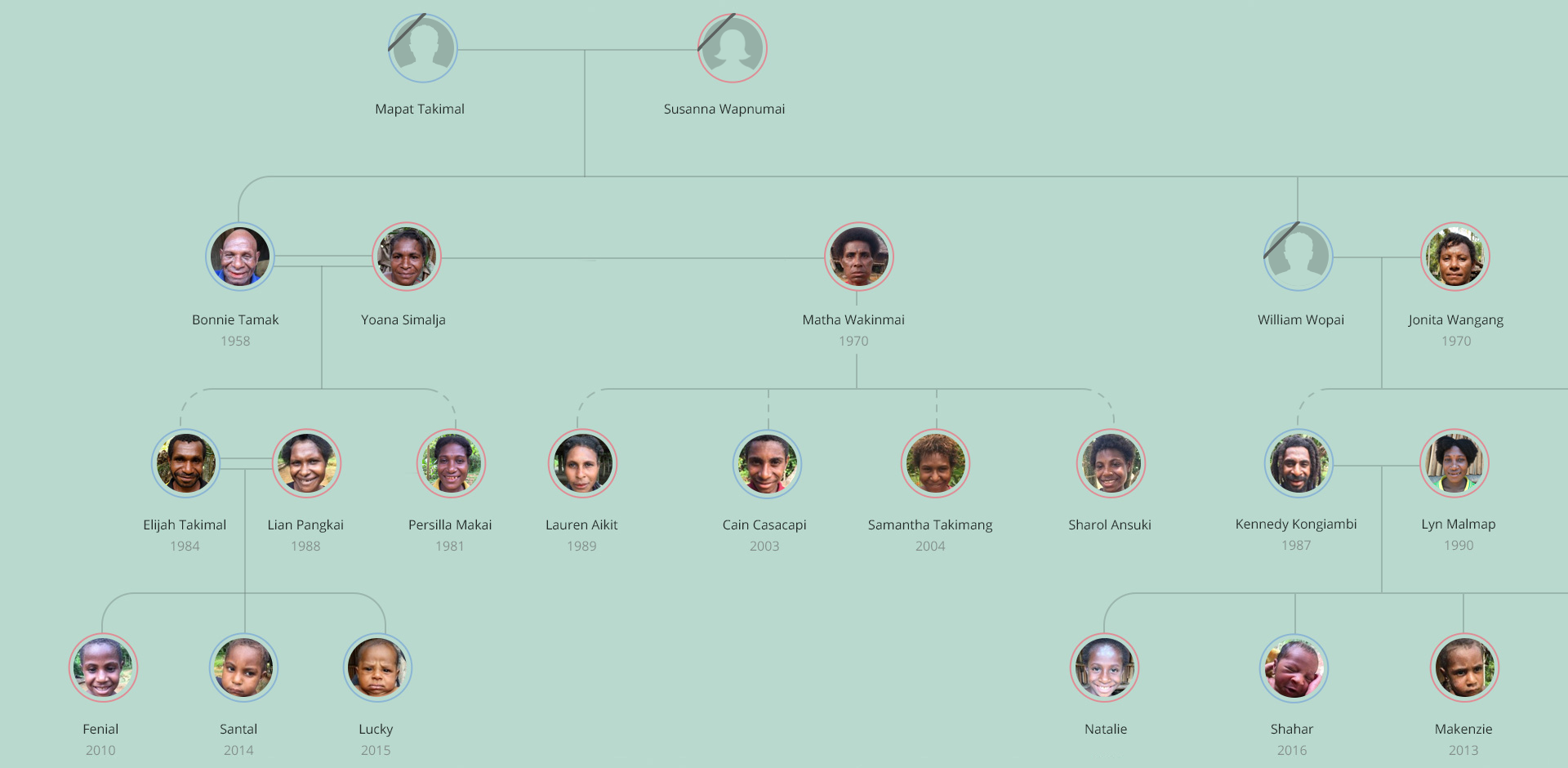

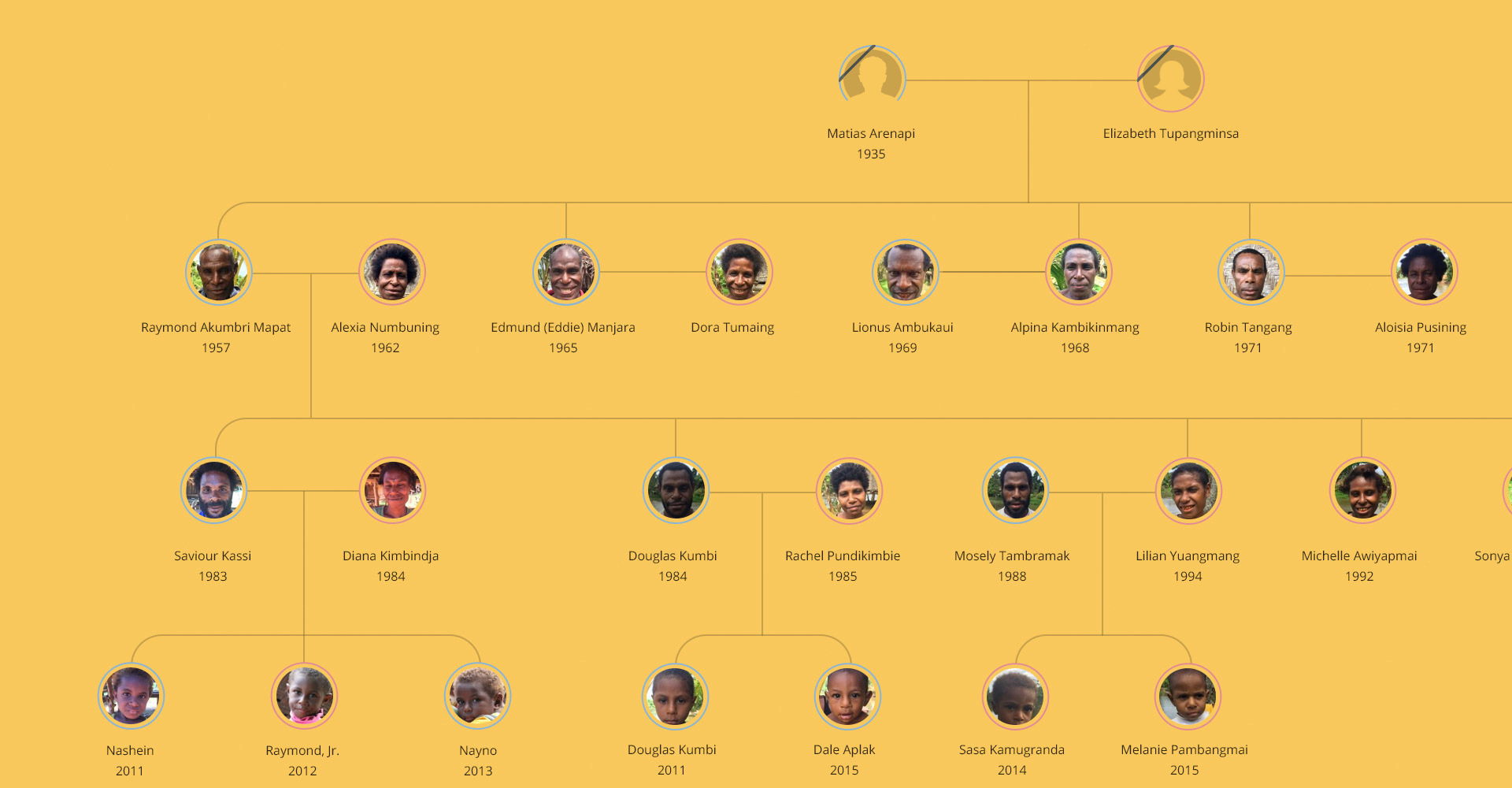

Bonnie's family

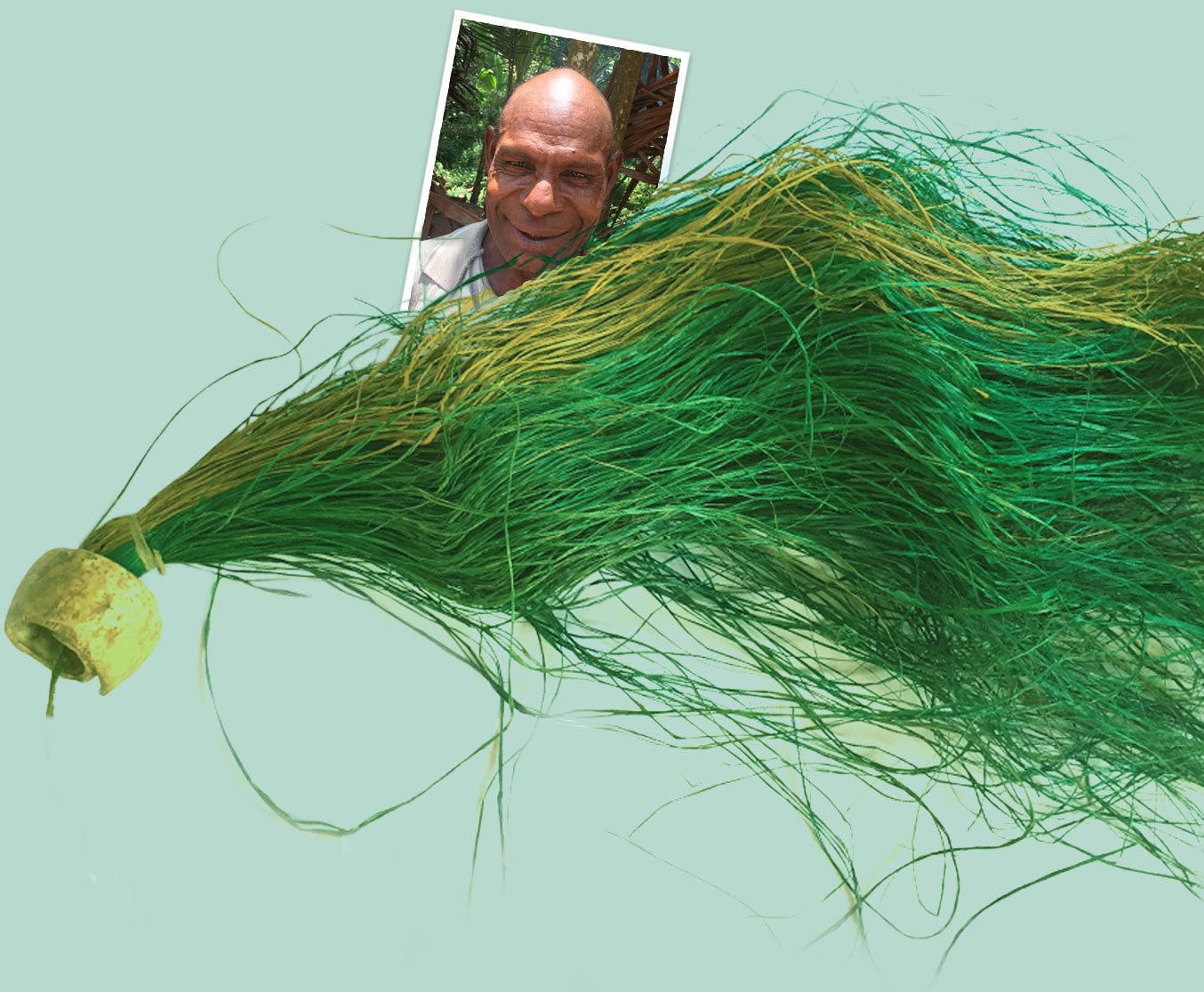

Hornbill totem

His father was in debt, so

he had to give the boy as payment.

Adopting is simple: you just take in the child and provide for him. Now I am his parent.

We couldn’t have children. We were heartbroken. My sister saw our sadness,

so she gave us her baby girl to be our daughter.

A cursed branch

Bonnie’s relative Paul has had a hard life: he lost his wife and two of his children to disease. An uncle adopted Paul’s surviving child, and Paul never remarried.

My wife died, and I knew that the second choice won't be the same as the first choice.

I did not want to marry again

so I decided to become a preacher.

Ambrose's family

Cassowary totem

When he was a young boy

he was sent to live in the spirit house

for eight weeks and he was trained to be a head hunter. After, he killed three people from the other tribes.

Sing sing ceremony

In Papua New Guinea, tribes gather to showcase their cultural dress, dances, and songs in the “sing sing” festivity. Sing sings are an opportunity to show off the strength of the tribe, to mark an upcoming marriage, and to make peace between warring tribes.

Sing sing is so important, because it’s when

our young people can take pride in traditions from the old days.

Raymond's family

White parrot totem

We forgot a lot after the missionaries came.

Now we try to get it back. With outside culture, mess and corruption came. It is important to look back to the old ways to make order.

Chewing betel nut

The betel nut is the seed of the areca palm tree. Known to cause a stimulating effect, chewing betelnut is part of the tribal spiritual practice. Chewing betel nut reddens the mouth — and can cause severe dental problems.

You have to chew betel nut and

the spirits come to you and you can talk to them.

They come into your body and make you do what you need to do. The spirits are our ancestors.

Crocodile skin

At age 25, Raymond’s son Douglas was sent to the spirit house to receive patterned cuts to his skin as part of a rite of passage undertaken by all men in the Karim tribe. Douglas stayed in the spirit house for six weeks to prepare, and then his eldest paternal uncle applied the cuts. The pattern is known as “crocodile skin”.

Jack's family

Crocodile totem

A great eagle flew off to Manam Island, where there is a volcano. It scooped up some fire in a coconut shell and flew back here.

He dropped it on this land, and it became Yimas.

I’m glad we are building a family tree. It allows us to prove to the authorities that

the land belongs to us, and will belong to our descendants.

Mitchell’s family